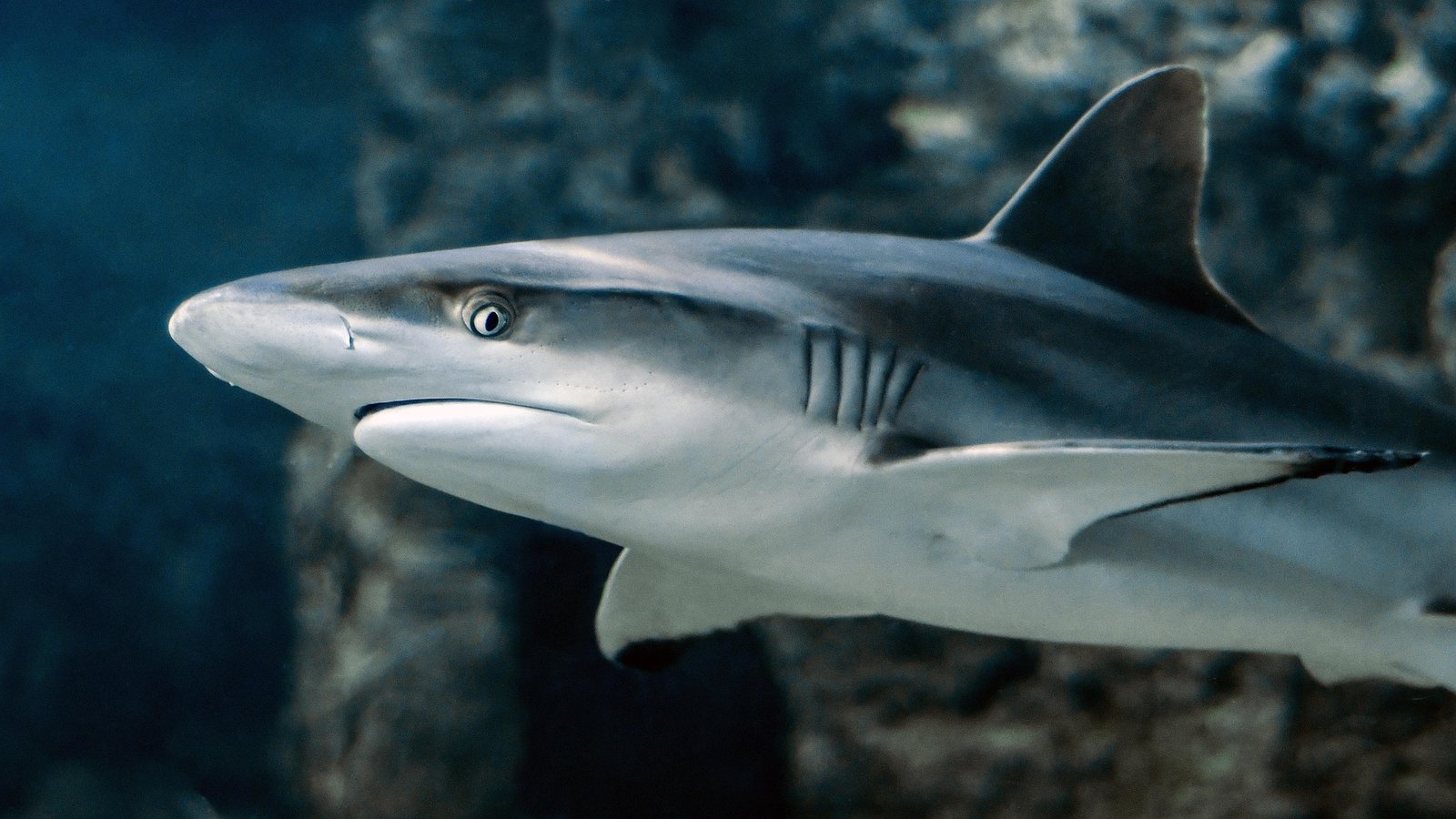

Sharks have evolved over hundreds of millions of years to become some of the ocean’s most efficient hunters. With highly specialized senses, adaptive behaviors, and finely tuned physical traits, these apex predators play a critical role in maintaining balance in marine ecosystems. Their hunting strategies vary widely between species, shaped by habitat, diet, and body structure. However, despite their formidable reputation, shark behavior is often misunderstood, particularly in terms of how they detect, stalk, and capture prey.

Understanding how sharks hunt offers a fascinating glimpse into the biological precision of these animals. From using electroreception to detect hidden fish to ambushing prey from below, sharks rely on a suite of adaptations that make them perfectly suited for survival in diverse ocean environments.

The Role of Sensory Perception

One of the key advantages sharks possess is an exceptional set of sensory systems that help them locate prey even in low visibility. Their eyesight is adapted for both day and night hunting, with some species able to detect light levels far lower than what the human eye can perceive. This gives them an edge in deep or murky waters where light is limited.

In addition to vision, sharks have acute olfactory senses, capable of detecting minute concentrations of substances in the water. For instance, some species can detect a single drop of blood in millions of gallons of seawater. This keen sense of smell enables them to follow scent trails over long distances until they locate the source.

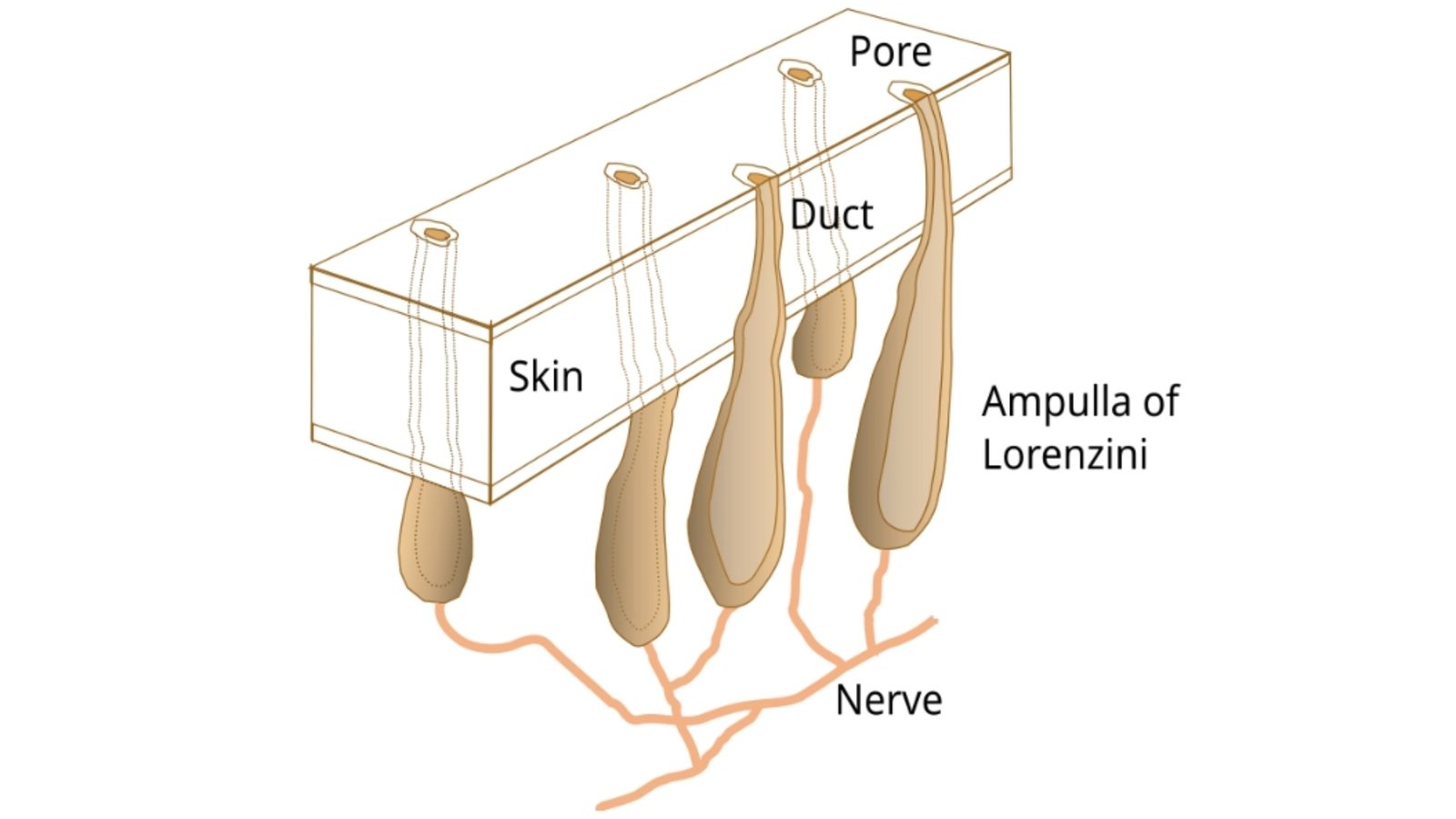

Electroreception and the Ampullae of Lorenzini

Sharks have a unique ability that sets them apart from most other marine predators: electroreception. Specialized sensory organs called the ampullae of Lorenzini are located around their snouts, allowing them to detect the faint electric fields produced by the muscle contractions of other animals. This adaptation is especially useful when prey is hidden beneath sand or sediment.

These organs are so sensitive that sharks can detect electrical signals as subtle as the heartbeat of a fish. During the final stages of an attack, this capability helps them pinpoint the exact location of their target. It is particularly effective for bottom-dwelling species like the hammerhead, which often uses its wide head to scan the seafloor for rays and other buried prey.

Stealth, Speed, and Surprise

Many shark species rely on stealth and patience when hunting their prey. Instead of charging directly at prey, they often approach slowly or remain still until the perfect moment to strike. For example, great white sharks use a technique known as “ambush predation,” rising rapidly from below to surprise seals at the surface. This behavior is frequently observed in regions like Seal Island, South Africa.

The shape and build of a shark’s body influence its hunting strategy. Fast-swimming species like the shortfin mako rely on high-speed chases to catch agile prey such as tuna. Their streamlined bodies and powerful tails enable them to achieve quick bursts of speed, which are essential when pursuing fast-moving targets.

Hunting in Groups and Opportunistic Feeding

Although most sharks are solitary hunters, some species are known to cooperate during feeding. The blacktip reef shark, for example, may participate in group hunts, where several individuals work together to herd schools of fish into tighter clusters. This behavior increases the chances of a successful catch for each shark involved.

Other species are opportunistic feeders that adjust their approach according to the situation. Tiger sharks are a prime example. They are not selective hunters and will eat a wide variety of prey, including sea turtles, fish, and carrion. Their strategy involves inspecting potential food sources with frequent test bites, relying on a combination of curiosity and persistence.

Tracking Migrating Prey Across Vast Distances

Some sharks travel great distances to follow seasonal migrations of prey species. For instance, the scalloped hammerhead has been observed traveling between coastal nurseries and offshore seamounts to hunt schooling fish. These long-distance journeys are guided by environmental cues, including temperature gradients, ocean currents, and prey availability.

Blue sharks and oceanic whitetips also cover large areas in search of food. Rather than defending a territory, these pelagic hunters roam the open ocean, relying on patience and sharp senses to locate prey. This roaming behavior reflects a strategy of maximizing opportunity rather than targeting specific species or locations.

The Role of Age and Experience

Sharks are not born as expert hunters. Young sharks must learn to hunt effectively, often through trial and error. Juvenile sharks typically feed on smaller, less challenging prey, allowing them to build the skills needed for more complex hunting behaviors as they mature.

Experience plays a key role in refining these behaviors. Older sharks often show greater success in capturing prey, as they have learned to recognize patterns in movement, concealment, and timing. This gradual development highlights the cognitive complexity involved in shark hunting.

Final Thoughts

Sharks are far more than mindless predators. Their hunting techniques reveal a high level of adaptation, sensory sophistication, and strategic thinking. Each species has evolved its own approach to finding and capturing prey, shaped by millions of years of evolution and ecological pressure.

By understanding how sharks hunt, we gain not only a deeper appreciation for their intelligence and ecological importance but also a more balanced view of their role in the marine world. Dispelling myths and embracing the science behind shark behavior helps foster respect for these vital creatures and the ecosystems they help sustain.